As humanity inches closer to becoming an interplanetary species, the question of how Earth's creatures will adapt to life beyond our atmosphere grows increasingly urgent. While much research has focused on human physiology in space, scientists are now turning their attention to a previously overlooked aspect of interstellar living: how our animal companions might fare in the void. The emerging field of microgravity ethology promises to revolutionize our understanding of animal behavior when the familiar pull of gravity disappears.

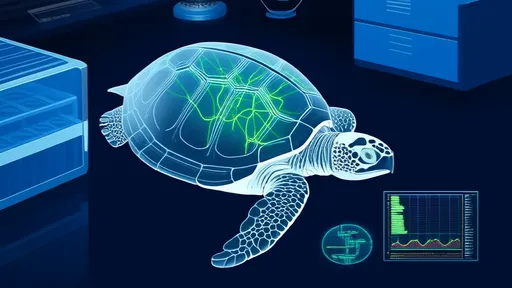

The concept of space pet habitats, colloquially called "pet pods," has evolved from science fiction to serious scientific inquiry. Recent experiments aboard the International Space Station have provided tantalizing glimpses into how mammals, birds, and even reptiles respond to weightlessness. Unlike the structured experiments of early space programs, contemporary researchers employ sophisticated monitoring systems that track everything from circadian rhythms to social interactions in confined orbital environments.

Behavioral specialists note that predicting animal reactions to zero gravity involves more than simply observing physical adaptations. The psychological impact of perpetual free-fall conditions may prove more challenging than the physiological changes. Early observations of mice in orbital laboratories revealed unexpected behaviors - some subjects adapted swimming motions to navigate their enclosures, while others entered states resembling torpor, possibly due to spatial disorientation. These findings suggest that different species, and even individuals within species, may demonstrate wildly varying responses to the same environment.

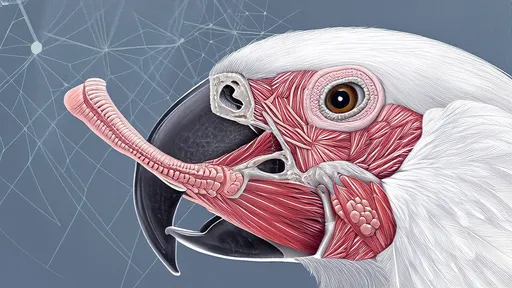

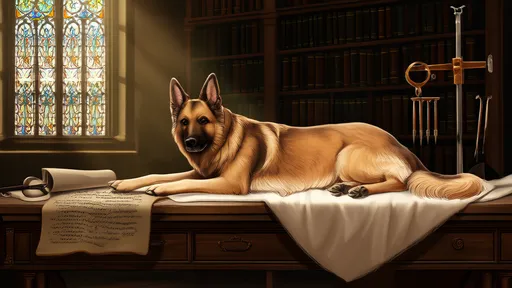

Veterinary space scientists have identified several critical factors that influence animal adjustment to microgravity. Body mass and morphology play obvious roles - creatures with lower mass find movement easier, while those with specialized locomotion (like snakes or spiders) face unique challenges. More surprisingly, an animal's typical orientation to gravity on Earth strongly predicts its space adaptation. For instance, tree-dwelling species accustomed to three-dimensional movement often outperform ground-dwelling counterparts in early trials.

The development of specialized pet containment systems has become a priority for space agencies and private aerospace firms alike. Modern prototypes incorporate rotational elements to simulate gravity, multisensory stimulation to prevent boredom, and fail-safe restraint systems for launch and landing phases. Designers face the unique challenge of creating environments that feel secure to animals while allowing for natural behaviors - a balance never before attempted in terrestrial pet habitats.

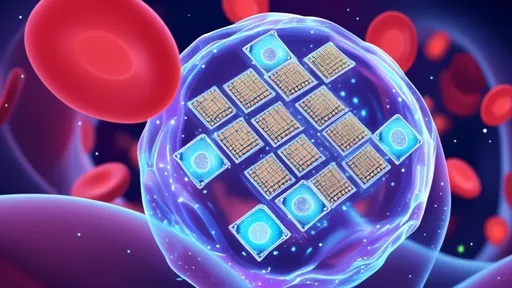

Perhaps the most groundbreaking revelations come from neurobiological studies of animals exposed to prolonged weightlessness. Brain scans reveal that the vestibular system - responsible for balance and spatial orientation - undergoes remarkable plasticity when deprived of gravitational cues. This neural adaptation occurs faster in younger animals, suggesting that pets born in space might develop fundamentally different sensory processing than their Earth-born ancestors. Such findings raise profound questions about the long-term viability of terrestrial species in off-world colonies.

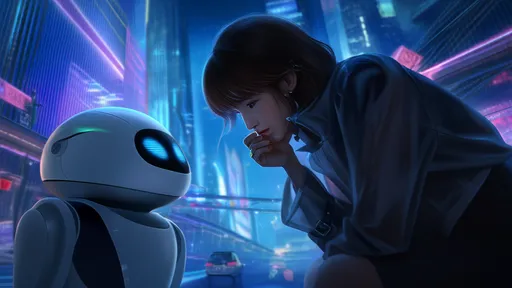

Ethical considerations permeate every aspect of space animal research. Advocacy groups demand rigorous standards for orbital pet care, citing the inability of animals to consent to such extraordinary living conditions. Researchers counter that understanding animal adaptation provides crucial insights for human space habitation while developing technologies that may eventually allow pets to accompany settlers on long-duration missions without compromising welfare.

Looking ahead, the field stands at the threshold of transformative discoveries. Planned experiments will expose diverse species to variable gravity fields, social isolation scenarios, and extended orbital habitation. The data may not only inform future space pet care but could rewrite our fundamental understanding of how gravity shapes behavior across the animal kingdom. As commercial space travel looms, these studies take on urgent practical importance for families contemplating off-world relocation with their non-human members.

The psychological bond between humans and animals adds another layer of complexity to space habitation equations. Behavioral specialists warn that depriving space colonists of animal companionship could have detrimental effects on mental health, making successful pet integration a matter of crew welfare rather than mere sentimentality. This realization has spurred investment in pet pod technology from unexpected quarters, including mental health foundations and corporate space settlement initiatives.

What emerges from current research is a nuanced picture of animal resilience and adaptability. While early predictions suggested universal distress in weightless conditions, the reality proves more varied and fascinating. From cats learning to "swim" through air to birds adapting their flight techniques for enclosed spaces, Earth's creatures demonstrate remarkable problem-solving capacities when faced with this most alien of environments. These observations fuel optimism about interspecies expansion into the solar system while reminding us how much remains to be learned about our fellow travelers on this planet.

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025