The release of non-native bird species into the wild has become a growing concern among environmentalists, lawmakers, and conservationists worldwide. While the act of freeing birds may seem like a compassionate gesture, the ecological and legal ramifications can be severe. Governments are increasingly tightening regulations to prevent the unintended consequences of releasing foreign species into local ecosystems. This article explores the legal boundaries and ecological risks associated with the practice, offering insights into why such releases are often prohibited.

The Ecological Impact of Non-Native Species

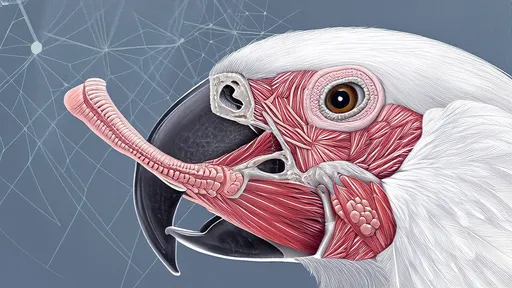

Introducing non-native bird species into an environment where they do not naturally occur can have devastating effects on local biodiversity. These birds may compete with native species for food, nesting sites, and other resources, often outcompeting them due to a lack of natural predators. In some cases, invasive species have driven native birds to the brink of extinction. For example, the introduction of the European starling in North America has led to significant declines in populations of native cavity-nesting birds.

Beyond direct competition, non-native birds can also introduce diseases to which local species have no immunity. Avian malaria, for instance, has decimated native Hawaiian bird populations after being introduced through exotic species. The disruption of food chains and the alteration of habitats are additional consequences that can take decades to reverse, if they can be reversed at all.

Legal Frameworks Governing Bird Releases

Many countries have enacted strict laws to regulate or outright ban the release of non-native bird species. In the United States, the Lacey Act prohibits the import, transport, or release of any wildlife deemed harmful to agriculture, horticulture, or native species. Violations can result in hefty fines and even imprisonment. Similarly, the European Union’s Invasive Alien Species Regulation requires member states to take measures to prevent the introduction and spread of non-native species.

In Australia, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC Act) lists specific species that cannot be released into the wild. Penalties for non-compliance can reach up to hundreds of thousands of dollars, reflecting the seriousness with which governments view the issue. These laws are not merely bureaucratic hurdles; they are designed to protect fragile ecosystems from irreversible damage.

The Ethical Dilemma of Bird Releases

While the intention behind releasing birds—often tied to religious or cultural practices—may be noble, the ethical implications are complex. Releasing captive-bred birds that lack survival skills can lead to their slow demise from starvation or predation. Additionally, the practice may inadvertently support illegal wildlife trade, as many birds sold for release are captured from the wild or bred in questionable conditions.

Conservationists argue that there are more ethical alternatives, such as supporting habitat restoration or donating to wildlife rehabilitation centers. These actions contribute to the well-being of native species without introducing new ecological threats. Public education campaigns are also crucial in shifting perceptions about what constitutes a truly compassionate act toward wildlife.

Case Studies: Lessons Learned

History offers several cautionary tales about the dangers of releasing non-native birds. In Singapore, the red-breasted parakeet, an introduced species, has become invasive, outcompeting native birds like the oriental pied hornbill. Efforts to control its population have proven costly and challenging. Similarly, in the UK, the ring-necked parakeet, originally from Asia and Africa, has spread rapidly, causing damage to crops and native wildlife.

On the other hand, some regions have successfully implemented programs to manage or eradicate invasive species. New Zealand’s rigorous biosecurity measures, for example, have prevented several potential ecological disasters by intercepting non-native birds before they could establish populations. These cases underscore the importance of prevention and swift action in mitigating risks.

Moving Forward: Responsible Practices

To balance cultural practices with ecological responsibility, some communities have adopted compromise solutions. In Taiwan, for instance, authorities organize controlled releases of native species in designated areas, ensuring that the practice does not harm local ecosystems. Such initiatives demonstrate that it is possible to respect traditions while safeguarding biodiversity.

Individuals can also play a role by reporting sightings of non-native birds to local wildlife agencies, helping to track and manage potential invasions. Advocacy for stronger enforcement of existing laws and support for conservation programs are additional ways to contribute to the protection of native ecosystems.

The release of non-native birds is a practice fraught with ecological and legal pitfalls. While the motivations behind it may be well-meaning, the consequences can be dire for native wildlife and habitats. Stricter laws, public education, and ethical alternatives are essential in addressing this issue. By understanding the risks and adhering to legal guidelines, we can help preserve biodiversity for future generations.

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025