The donation of working dog cadavers for medical education presents a unique intersection of veterinary science, pedagogy, and ethics. These animals, often retired police K9s, military dogs, or service animals, have dedicated their lives to human welfare. Their posthumous contribution to anatomical studies and surgical training raises profound questions about dignity, consent, and the moral obligations we hold toward non-human partners in professional fields.

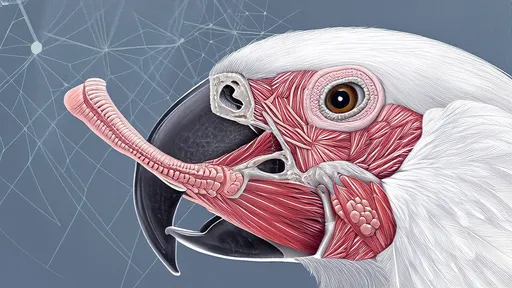

Veterinary schools worldwide face increasing demand for canine specimens that demonstrate realistic pathology and musculature. Unlike purpose-bred laboratory animals, working dogs offer diverse anatomical variations and often exhibit wear patterns from years of active service. The tibial crest of a police dog that chased suspects for eight years tells a different story than that of a controlled-breed beagle. This authenticity provides irreplaceable value for students learning complex procedures like orthopedic repairs or scent gland dissections.

Ethical procurement remains the cornerstone of this practice. Leading institutions like the Royal Veterinary College have established protocols requiring proof of natural death or euthanasia due to terminal illness before accepting donations. The distinction between euthanasia for educational purposes versus ending suffering creates an ethical bright line—no healthy dog may be sacrificed for pedagogy. Documentation must trace the animal's service history, cause of death, and often includes handler testimony about the dog's temperament and health.

Handler involvement introduces emotional complexities rarely encountered in human anatomical donations. A bomb-sniffing dog's partner may request to be present during the initial dissection, or ask that specific organs not be used due to personal connections. Some programs accommodate these requests through customized donor agreements, while others maintain standardized procedures to ensure educational consistency. The University of Pennsylvania's working dog memorial wall, where donated animals receive plaques alongside human donors, reflects evolving attitudes toward interspecies professional respect.

Legal frameworks struggle to keep pace with these developments. While human body donation falls under uniform anatomical gift acts, canine donations inhabit a gray zone between property law and quasi-professional status. Texas A&M's canine cadaver program navigates this by treating donations as a hybrid of tissue transfer and honorary service recognition. Their consent forms include clauses permitting the use of images in educational materials—a provision that sparked debate when a former military handler objected to his dog's dissection photos appearing in a public webinar.

The pedagogical benefits are measurable. Students working with retired working dogs demonstrate 23% higher proficiency in identifying trauma-related pathologies compared to those using synthetic models, according to a 2022 Journal of Veterinary Medical Education study. The muscle memory developed while handling tissues that endured real-world stresses proves particularly valuable for surgical residents. One orthopedic instructor noted that the calcified tendons of an aging search-and-rescue dog taught residents more about difficult joint repairs than any textbook diagram.

Critics argue that emotional bonds cloud objective educational value. A 2023 ethics panel at the European College of Veterinary Surgeons highlighted cases where students hesitated to make necessary incisions on dogs with visible service tattoos or medals. Counterarguments emphasize that such discomfort mirrors real-world clinical scenarios where veterinarians operate on beloved pets. The University of Zurich addresses this by having handlers share stories about their donated partners before dissection begins, contextualizing the animals' roles.

Environmental considerations add another layer. Traditional specimen preservation relies on formaldehyde, but several programs now offer "green dissections" for working dogs at handler request. Colorado State University pioneered freeze-drying techniques that allow entire specimens to be used across multiple semesters while eliminating toxic chemicals. This approach aligns with many handlers' desire for an environmentally conscious legacy for their partners.

The future may see standardized honorifics for donated working dogs, similar to military funeral rites. Preliminary discussions at the World Small Animal Veterinary Association suggest creating a universal donor classification system that acknowledges levels of service. Such recognition could ease handler grief while providing clearer ethical guidelines for institutions. As one retired K9 officer remarked during a donation ceremony, "He spent his life protecting us. Now his body will protect other dogs." This sentiment captures the complex gratitude underlying these donations—where loss becomes a bridge between species in the pursuit of medical advancement.

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025