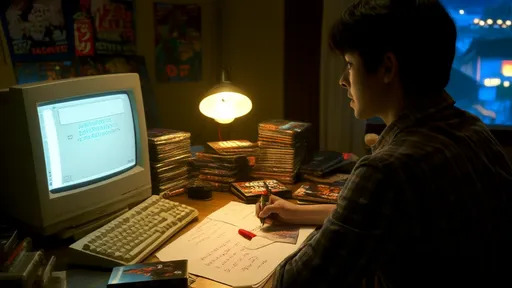

In the dimly lit internet cafes of late 1990s China, a cultural revolution was brewing—not through political pamphlets or underground music, but through pixelated Japanese role-playing games and American first-person shooters. The unlikely architects of this revolution weren't corporate giants or government initiatives, but rather loose collectives of passionate gamers operating under pseudonyms: the legendary Chinese fan translation groups, or "Hanhua Zu".

These underground linguists performed what academics now call "guerrilla localization"—hacking into game code, painstakingly replacing thousands of lines of text, then distributing their handiwork through clandestine BBS forums and burned CDs wrapped in photocopied manuals. Their work formed the backbone of gaming literacy for an entire generation, creating what scholar Li Wei calls "a parallel education system for global pop culture."

The Golden Age of Piracy as Cultural Exchange

Before Steam's 2015 China debut and PlayStation's official 2014 market entry, these translation collectives operated in a legal gray zone that scholars compare to Soviet-era samizdat publishing. A single translated RPG could pass through dozens of hands, each adding annotations—creating what Peking University media professor Zhang Xia calls "crowdsourced cultural footnotes."

Particularly influential was the 2002 Chinese patch for Final Fantasy VII, which introduced narrative complexity previously unseen in domestic media. The translation's poetic liberties—rendering "Aerith's Theme" as "The Flower That Blooms on the Rooftop"—still echo in Chinese gaming discourse today.

Technical Innovation Through Necessity

Facing hardware limitations, these groups invented techniques now standard in professional localization. The 3DM collective's 2005 workaround for displaying Chinese characters in Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion—by hijacking the game's Japanese font support—later inspired official localization tools. Former Hanhua member turned Tencent localization director Chen Yu recalls: "We had to rewrite entire dialogue trees when text overflowed the text boxes. This forced us to master concise, impactful writing—a skill I use daily."

The groups' technical documents, shared through encrypted forums, became accidental textbooks. A 2008 tutorial on hex editing by translator "WindySnow" remains required reading at Shanghai Game Studio's training program.

Cultural Mediators Beyond Translation

These groups didn't merely translate—they contextualized. The "Blue Sky" collective's legendary 60-page companion booklet for Chrono Trigger included explanations of Japanese Shinto motifs, analyses of character arcs, and even comparisons to classical Chinese literature like Journey to the West.

This pedagogical approach shaped China's game development scene. Moon Studio CEO (Ori and the Blind Forest) Thomas Mahler acknowledges: "Our Chinese partners' deep RPG literacy—all stemming from those translated manuals—fundamentally improved our narrative design."

The Legacy in Today's Industry

As China's gaming market surpasses $45 billion, former Hanhua members now lead major studios. The founder of MiHoYo (Genshin Impact) began in a Xianxia game translation group, while NetEase's chief localization specialist honed her skills localizing Baldur's Gate mods.

Yet the groups' true legacy lives in player expectations. Chinese gamers' renowned sensitivity to localization quality—rejecting even professional translations deemed "too literal"—stems from those meticulously crafted pirate editions. As Steam's current top-reviewed Chinese translator "Ash" notes: "We're still chasing the standard set by those amateurs working on CRT monitors twenty years ago."

The story of Chinese game localization groups isn't just about piracy—it's about how cultural barriers were dismantled by passionate amateurs, one painstakingly translated line of dialogue at a time. Their work, though legally ambiguous, constructed the foundation upon which today's global gaming exchange stands.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025